|

There once was a thing so huge you could hear the floorboards creak as it moved around the house; you could swim in its footprints and wash in its snot. It would walk around and tear the tops off mountains and suck on the glaciers before crunching on the stone;

it would rip up the tall pines and use them to scratch its back and clean between its toes; it would use a sheep for an ear bud, a flock of them roped together with vine for a sponge, and when it went for a swim the tide came in. When it sneezed great hurricanes would rush through the town and rip the washing off the lines, and when it farted a great sulphurous fog would fall, and everyone would shut their windows for a month.

|

|

These were the times I grew up in and everything was better then. We had some fun in those days.And fun was funner then: one time my grandparents came round for Christmas and grand papa told a joke and my Nana she laughed for a whole year - she was still chuckling when they came back next Christmas and when he told it again she laughed for a year and a half. I wasn’t till summer she got her breath back and said it was funnier the second time round. He never told a joke again. In fact he never spoke again, he would just open his mouth and Nana would start to chuckle saying, “No, no I can’t take it, shut your trap.” And he would close it without a whisper. I still smile when I see his poor doleful face just itching to tell that joke again.

|

|

We would tease him until he went so red in the face that steam came out of his ears. We put a kettle on his head to make tea and it boiled so fast that in the end it exploded and blew the roof off the kitchen. Nana didn’t mind, she just called it her conservatory and moved in her tomato plants. They grew big and red but never so red as grand papa.

|

|

Artists would come to the town to try and catch the colour of my grandfather’s face. Picasso arrived and for months he sat there mixing his paints, throwing it on the canvas and holding up the picture to my poor grand papa’s crimson features. He gave up in the end… I believe that was when he discarded conventional painting and took up with his blue period, red was then forever a disappointment to him.

|

|

| All around here was a forest once, where light would never dare to show its face, all was dark as night, a dappled shadowy place to be sure, where lurked creatures made of mist and shade that would wrap themselves around you to feed on your warmth. Wraiths they were, wary shy things really, that I didn’t mind giving what I had to spare if I’d had a good hearty breakfast of sawdust and stew, but at night after a hard day’s tarrying when the black took on a darker hue - those were the times when they were less welcome. There were those I knew who had succumbed to the cold embrace of the wraith, they would sit slumped against a tree ready to be absorbed by trunk and leaf mould into the forest floor, food for the cycle of life. They meant no harm you see, sustenance was all they craved and if one was to come across one of these poor fellows, all that could be done was to let loose a hot stream of piss upon them. This was manna to the wraith and a reviving shock to the fellow. The two would part and many’s the old friend I’ve had to fight off angry at being freed from that seductive embrace. |

|

There’s an art to woodcutting: the swing of the axe, the heft of the shaft, the buttery feel of a sharp blade slicing through bark and stem, wood and pith, the resinous tang of the tree’s juices spilling into the air and the rhythmic pound of muscle, iron and wood resounding through the forest. My father had the knack of it, he could fell an acre a day and a wood in a week. He wandered far and wide, never to be seen but for the distant fall of green and the crack and thunder of felled trunk leaving a swathe of churned black earth in his wake.

|

|

Great fields of gold and yellow would spring from the soil with the sweet aroma of corn and rape; he was the life giver, the bringer of food and fire, a fearsome hero and a frightening and vengeful god.

|

|

| My mother was a different animal altogether, a radiant source; she had no need to fear the forest, no quest to tame. The wraiths would gather at her touch, swarm over her body and bathe in her light, for her they gave rather than took. She would depart each night with a farewell kiss and return each morning shining with a sated glow. It was said that she warmed the bed of every home in our village - and the next - and the next - and when she gave out exhausted in the end it was a grateful country that awarded her the highest medal in honour of her selfless generosity. My father was less appreciative of her liberality than possibly he could have been. |

|

Her brother, my uncle, was cast from a similar mould. Bees would gather to him in a buzzing cloud, the resonant hum of which had struck him deaf. Like my mother he had bright red hair through which would crawl the laden bees shaking loose their fragrant load. His tongue would snake out to lick the honey from the hives nestled in his beard and he ate nothing else but the heady aroma of the mixture of pollen that fell around his face like snow. Every orchard, every field, every blossom or flower around was indebted to him and his bees and the districts through which he walked had the finest fullest crops the whole world round. To see my mother and her brother together was to see the sun and moon both shine together in the same sky.

|

|

It came to pass that my mother brought to me a sister, a delicate shimmering thing that slipped into this world half here, half not, sparkling like a waterfall and she grew so fast you could see the rain running off her back as she ran. I loved to play hide and seek with her, run and swim with her until one day she pulled away with such effortless strokes that it seemed the water coursed through her rather than around.

|

|

It was about this time that a storm began to gather around our home. My father returned and there was a hot rage in the air and the halls echoed with his roar until one day I woke up and the door had been split in two by his axe. My mother came to me then distraught.

|

|

“I cannot halt this thing, your father will bring disaster upon us all, he is under the mistaken belief that he is cuckolded in the manner of the conception of your sister and I cannot convince him otherwise, even if I were to raise a thousand ancestors in my defense. He is inflamed and will destroy the balance of our times. We will all be asked to choose sides in the coming battle; I do not plead with you to take mine, but I ask that you care for your sister and protect her with all the means at your disposal.”

I protested but she silenced me

|

|

“There is another, blackened not by the rays of the sun nor by some inheritance of race, but from the oily tar that oozes from his skin. The hairs that cover his body are coated in pitch, and on a cool day with the wind blowing he takes on the silvery grey hue of weathered wood, but with the sun high or when turned to anger, the flames lick his skin, feeding on the rising vapour. He feels no harm, the fire dances just above the surface of him in an ecstasy of existence, curling over his arms and writhing around his hair and face which with a breath he can extinguish but with a blow he can raise to an inferno blazing with a white hot heat; it is as if to be confronted by the sun and as useless to oppose. I warn you we are in trouble.”

|

|

My father’s anger knew no bounds, he didn’t dare to confront my mother openly; her strength, though appearing soft, was still too much for him without allies. He pursued them avidly but found himself thwarted at almost every turn by mother’s skill at enjoining others to her cause. He did however find one, this artisan of fire, and through him eventually an army men either affeared of my father and his ally or the sort who would take to battle in the service of almost any cause, the sort that loves the smell of blood and thunder.

He declared war on his own family, the forest that enveloped it and our village. He began from the outskirts and we hardly noticed at first, it was the wraiths that appeared in ever-greater numbers, gathering around the house at night, wailing with their mournful song that gave sound to that silence. The air then hung with mist but still through it we could see the fire raging and hear the cries of our friends and trees falling. It was then my father cam

|

|

My mother, sister and myself were confronted by him one frightful night as the flames burnt in an ever decreasing circle around us

“I will take what’s yours, it will be mine by might and you, you woman have forfeited any rights by giving birth to this abomination, if you will move away I will claim my son.”

My mother said nothing, moved not, held my sister and looked to me.

“You are a fool father, more stupid than a rock and duller than the blade that’s been struck against it, you are possessed of the wit of the shit beneath my shoe and half as welcome”

“You would ally yourself against me. I will strike you down as an enemy of the clan, nothing will pass to you - you will be outcast”

“And yourself father - who will you be, friendless but for an army whose allegiance is weaker and less pleasing than the link of a child’s daisy chain? Stop this or stride a path to your own oblivion.”

“You are the fool and you are not now my son if you ever were”

“Then I relinquish all the burdens of your parentage. Go!”

And he left.

(MISSING ILLUSTRATION)

We fought for many days then, returning blackened by fire, cut by sword, chastened and chased till we had neither the will nor the wit to continue, but fight we did. I could talk of battle, friends and heroes lost. In the end it’s just blood and sadness, all is lost and only sleep remaining friend. I awoke to a sound that despite everything could still strike the fear into what remained of my soul, somewhere out there a floorboard creaked, and God forgive me I closed my eyes and pulled the covers over me. Don’t come to me.

|

|

It pulled me up, placed me in the palm of its hand, and held me to its face. I opened my eyes to a giant eye peering down at me, its pupil black like some endless disc of night into which I felt myself drowning, sucked insensible into its stupid depths. This was how I was to die. It was in the iris that its intelligence was revealed, the constant flexing of the muscle of the cornea, pulling contracting and expanding. From a distance you would have said they were brown, close up they are a kaleidoscopic marble of tones, flecks great rocks of colour.

|

|

I shout

“Fuck off”

“Shut your trap son!”

“Grandmother? Nana”

“Hug me grandson, I ain’t seen you in a while?”

“I can’t, you are too big”

“Big enough to crush you into bits… I could make a meal of you, mash you and smash you, you’d be my crunch and lunch, like those little yoghurt pots you see in the grocery”

“You are one bad nana”

“Where’s your sister?”

“She’s under the bed hiding”

“Come here girl, there, you ain’t scared of your grandma, are ya?”

She stretched a finger, and as she stroked my sister’s hair her face turned thoughtful

“I know my own kin when I see it. He’s a bloody fool.”

She put me down and turned to leave

“Now I got to get back, your grandpa will be wanting his dinner. Not a word about this to anyone or I might get hungry”

|

|

And for something that big she disappeared so fast I hardly believed she had been there at all.

The next day it was as if to wake from a dream into a nightmare. My sister said nothing but signalled me to look outside. There stood a great crowd of men massed around the house, some talking, some laughing, some gesturing or eating or drinking. They wore horned helmets, swords and swinging axes, these men who came with evil intent. We ran to mother who had been joined during the night by many other refugees. There was no sign of my grandparents. She smiled and gestured silence while she talked with the newcomers.

|

|

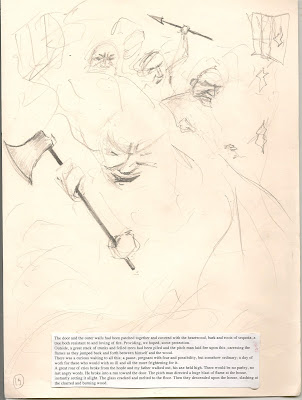

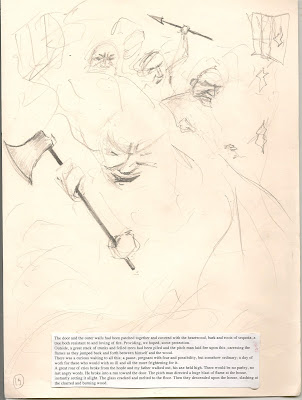

The door and the outer walls had been patched together and covered with the heartwood, bark and roots of sequoia, a tree both resistant to and loving of fire. Providing, we hoped, some protection.

Outside, a great stack of trunks and felled trees had been piled and the pitch man laid fire upon this, caressing the flames as they jumped back and forth between himself and the wood.

There was a curious waiting to all this; a pause, pregnant with fear and possibility, but somehow ordinary; a day of work for these who would wish us ill and all the more frightening for it.

A great roar of cries broke from the horde and my father walked out, his axe held high. There would be no parley, no last angry words. He broke into a run toward the door. The pitch man directed a huge blast of flame at the house, instantly setting it alight. The glass cracked and melted to the floor. Then they descended upon the house, slashing at the charred and burning wood.

(MISSING ILLUSTRATIONS)

|

- The villagers with us cowered in fear while my uncle marched back toward the boarded openings. The wraiths swam forward, cooling the air for the bees that he directed after them. They swarmed through the shell of the house avoiding sword and flame to sip beneath the attackers’ armour. The wraiths streamed after them, bewitching any man who might fall for their spell.

My father smashed through the door and stood there bathed in flames. My mother, swathed in wraiths, advanced upon him, he raised his axe upon her and I ran at him in a blind rage, slipped under his guard and flung myself at his body, pushing him back a metre or two until he swatted me away like a fly.

All was chaos as the army retreated back from our defence. As I lay there in the dirt I saw about me warriors writhing in a moving cloak of black and amber. Others lay still, becalmed in the raging sea of war. I dreamt for a moment of success but as I raised myself I saw behind them a wall of armour readying itself to counter attack.

My mother, her brother and my sister - with the villagers behind them - came out of the blazing house till they came to where I lay, broken.

A thundering pound shook the ground and everyone looked around them. Then came one, and then another, until this army could barely stand. All thoughts of battle were averted while the earth broke and cracked around us.

Grandmother was coming to town.

Then she was there. One great foot planted in the burning pile, the other in front of my father.

”I’ve had just about enough of this!”

Mother shouted “where have you been?”

“I had to sort out grandpa’s breakfast - he’s a terrible trouble if he ain’t had his whale and eggs. I’m not too late am I ? I would regret that”

My father cried

“Mother, you have no place here” and swung his axe into her foot

“You want to play with me, boy?!”

“I ask you to leave”

He lifted the axe again and brought it down, pretty much severing her toe. Thick black blood pumped into the soil.

“Now is that any way to treat your mother, she who birthed you under the great world tree? She who sucked on the sap of the source to give you your strength?”

“It’ll grow back, this is not your battle.”

“All battles are mine son - and none, I just take a particular interest where my grand children are concerned.”

“No longer, mother. I disown them, they are not mine.”

|

From the severed toe something like a root slipped out through the blood and snaked into the earth.

He lifted the axe, severed another toe and moved away.

“And where do you go telling me what to do, who to love and who to not? Love flows like the river son - it goes where it will.”

“There’s been a drought here mother, and this is not my river.”

My father had shifted and struck at the other foot.

“Stop hacking at my ankle, it’s irritating?”

Roots now slithered from all her wounds.

“She is a bad wife mother, whatever you say”

“Now you would get it into your head to marry a fertility goddess; it was never going to be easy, son”

“She is no goddess ”

“I don’t think you appreciate your wife, son, I think you’ve got it all wrong”

“Whatever you think now mother: it’s irrelevant now, you’re rooted!”

|

|

She reached for him but he danced away, she tried to lift a foot but the roots held and she started to topple, and only just pulled herself back with an elaborate swaying of the hips and swinging of the arms that suggested she would be pretty good with a hula hoop. Everybody ran away from her in chaos and plunged into each other. In the resulting melée my sister ran into the arms of the pitch man, who burst into flame, evaporating my sister into mist. My mother cried pitifully, my father saw this and ran at the pitch man in a fit of madness and remorse; my mother ran after him to save him while the pitch man himself blazed like a blacksmith’s furnace -sending forth a blast that engulfed them both.

|

|

Grandmother screamed

“I’ve had enough of this”

She pulled her feet from the ground, grabbed the pitch man and popped him into her mouth while he still blazed.

|

|

Meanwhile the flames that had engulfed my parents were in turn enveloped by the mist that coalesced around them, dousing the flame in a great cloud of steam, which, when it cleared, revealed them in each other’s arms, embracing. The wraiths glowed white like angels rising into the sky to cool after the protection they had given them.

Nana reached down and picked me up.

“That was the hottest chilli I’ve ever had… I wouldn’t want to be around this town when he comes out the other end”

“It will be more than a year til anyone will be able to step outdoors”

The army disappeared in disarray and I mourned my sister, but grandma calmed me, blowing a cool breeze into the mist that remained; this condensed into the transparent form of my sister - water seemed to pour into her until she took on her human form, and we were then reunited.

Now if you feel this was all a lot of family trouble, let me tell you about the time we all went on holiday together…

|